Venezuela: The Fall of the Petrostate Oil, Power, and Collapse

ChatGPT said:

Once the envy of Latin America, Venezuela experienced a dramatic descent from oil-fueled prosperity to economic ruin and humanitarian catastrophe that has captivated — and horrified — the world for over a decade. What began as a bold experiment in resource nationalism has devolved into a textbook case of the “resource curse,” exacerbated by authoritarian governance, crippling international sanctions, and deepening geopolitical rivalries. As the nation marks another year of instability, experts warn that without sweeping reforms, Venezuela may never recover.

Economists have long cited Venezuela as a cautionary tale of how abundant natural resources can breed stagnation rather than growth. Blessed with the world’s largest proven oil reserves — estimated at 303 billion barrels — Venezuela boomed in the mid-20th century, funding a vibrant middle class and modern infrastructure. But overreliance on oil exports left the economy brittle, vulnerable to price swings and mismanagement. “Venezuela’s story is not just about bad luck with oil prices,” said Dr. Maria López, an economist at the Inter-American Development Bank. “It’s a chronicle of deliberate choices that prioritized ideology over sustainability.”

Nationalization: A Triumph Turned Toxic

The turning point came in 1976, when President Carlos Andrés Pérez nationalized the oil industry, creating Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA). Multinationals like Exxon, Mobil, and Gulf Oil were compensated at “book value” and ushered out, handing the government full control of a sector that accounted for 95% of export revenues. At the time, Pérez hailed it as “the final act of our independence,” and Venezuelans celebrated the windfall.

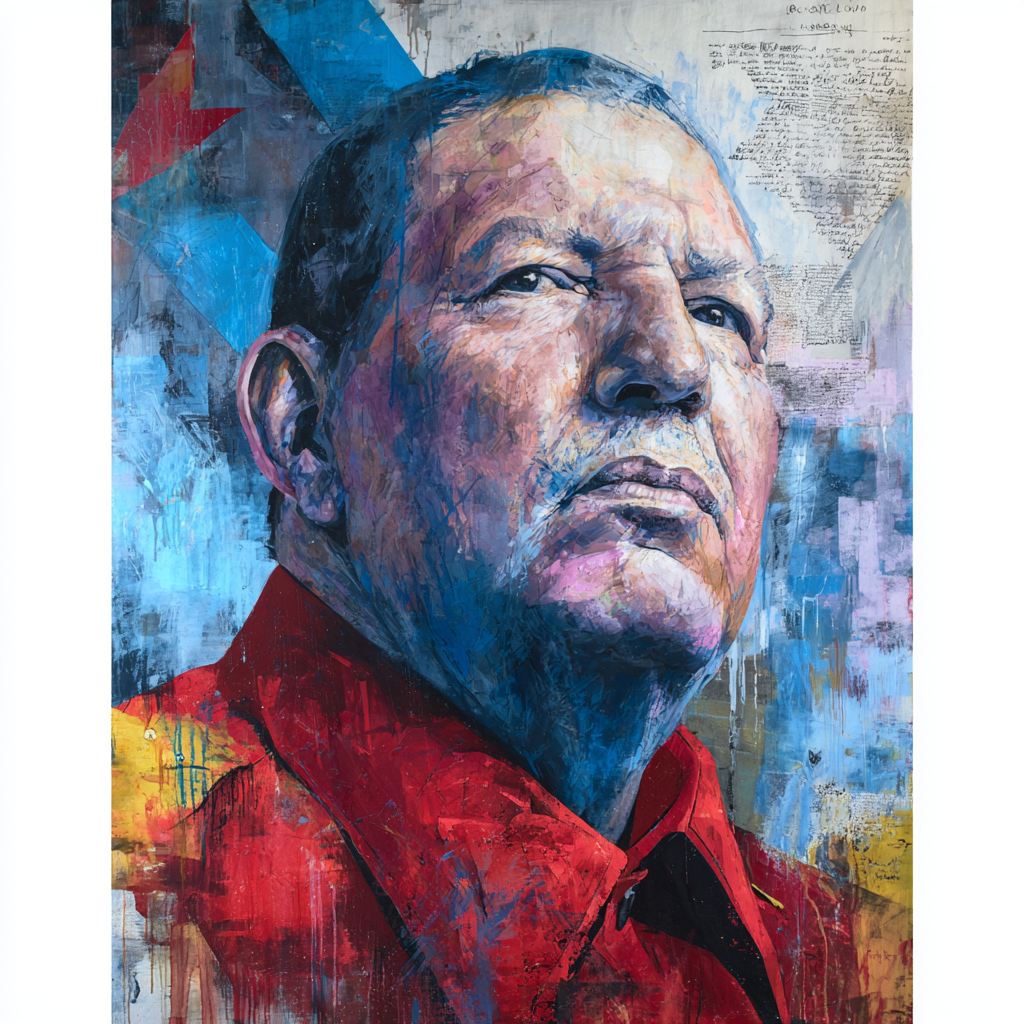

Yet, cracks soon appeared. PDVSA evolved from a world-class operator into a patronage machine. Under President Hugo Chávez, who took office in 1999, the company became a slush fund for socialist programs. Executives were picked for political loyalty, not competence, while billions vanished into off-budget initiatives and corruption scandals. Transparency International ranked Venezuela 176th out of 180 countries for corruption by 2016, with PDVSA implicated in schemes siphoning up to $300 billion, according to U.S. Justice Department indictments.

Chávez’s 2007 expropriations of foreign assets — including ExxonMobil’s $1.6 billion in fields — sparked arbitration battles that dragged on for years. Production plummeted from 3.5 million barrels per day in 1998 to under 500,000 by 2020, as infrastructure crumbled without investment.

Sanctions Seal the Collapse

The Chávez era’s policies laid the groundwork, but U.S. sanctions from 2017 onward delivered the knockout blow. Executive orders under Presidents Trump and Biden targeted PDVSA, barring oil sales to the U.S. and freezing $7 billion in assets. The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) reports that while the economy shrank 75% from 2013 to 2021 under Chávez and Maduro, sanctions amplified shortages, pushing inflation to 1.7 million percent in 2018.

By 2025, hyperinflation has eased somewhat through informal dollarization — with over 60% of transactions now in U.S. dollars or cryptocurrencies like Tether — but the damage is irreversible. Oil output hovers at 800,000 barrels daily, far below capacity, amid blackouts and unpaid workers.

A Humanitarian Catastrophe Unfolds

The human toll is staggering. More than 7.7 million Venezuelans — one in four citizens — have fled since 2014, overwhelming neighbors like Colombia (2.8 million refugees) and Peru. Hospitals lack electricity and medicine; infant mortality has doubled to 25 per 1,000 births, per UNICEF data. Malaria cases surged 76% from 2015 to 2020, erasing decades of progress.

In Caracas slums, residents like Ana Rodríguez, 42, barter goods amid blackouts. “We used to dream of oil riches,” she told The Global Herald. “Now, we dream of a full meal.” Crime syndicates thrive in the vacuum, with homicide rates at 40 per 100,000 — triple the global average.

Maduro’s Grip: Fraud, Gold, and Geopolitical Gambits

Nicolás Maduro, Chávez’s successor since 2013, has clung to power through contested elections. The 2017 vote for a constituent assembly saw turnout inflated by 1 million votes, as revealed by Smartmatic, the voting tech firm. The 2024 presidential election, marred by opposition disqualifications, prompted the U.S. to invoke Executive Order 13848 on election interference.

Isolation deepened in 2020 when Britain’s High Court blocked Maduro’s access to $1 billion in Bank of England gold reserves, recognizing opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president. “This ruling starves the regime of oxygen,” said Guaidó’s legal team.

Desperate, Maduro pivoted eastward. Russia supplied Sukhoi jets; China loaned $60 billion, repaid in oil; Iran sent fuel tankers. But alliances bred peril: In September 2025, U.S. forces under President Trump sank nine vessels — Venezuelan and Colombian — in the Caribbean, killing 47, for allegedly aiding Tren de Aragua traffickers. Caracas called it “piracy”; the U.N. Security Council debates its legality. Washington accuses Maduro of unleashing 10,000 criminals across borders as retaliation.

Venezuela, once deeply dependent on U.S. oil products, has shifted its supply chain towards Russia as sanctions and political tensions with the U.S. intensify. This strategic alignment highlights the nation’s struggle to maintain energy stability amid ongoing economic and governance challenges. For more details, read the full Bloomberg article

Dollar Shadows and a Fragile Recovery?

Amid the rubble, dollarization has stabilized prices, boosting retail by 20% since 2022, per the Central Bank. Remittances hit $4 billion annually, funneled via Bitcoin. Yet, it mocks state control: The bolívar trades at 40 million to the dollar on black markets.

What Lies Ahead?

Venezuela’s future hangs in the balance. Maduro’s 2025 term ends amid protests, with opposition leader María Corina Machado barred from running. International mediators push for talks, but experts like López doubt change without oil sector privatization and sanctions relief.

“This is a sobering lesson for Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and others,” said former PDVSA executive José Mendoza. “Oil is a blessing until it’s a curse.”

As dusk falls over Caracas’s derelict refineries, one thing is clear: The petrostate’s fall reshapes Latin America — and the world — for generations.

Elena Vargas reports from Caracas for The Global Herald. Additional reporting by Sofia Ramirez in Washington. This article is based on interviews, U.N. and World Bank data, and court documents.

![US official and [Diosdado Cabello] in secret meeting.](https://countrybrief.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/thumbnail-68-768x432.jpeg)